Introduction

Habits are a major portion of our lives. What we do day in and day out is roughly 90% or even more habit. Being more aware or what you're doing lets you have more choices. Being more aware also lets you recognize the results of your habits and reset your reward values. Changing your life for a richer future starts with being aware of you habits and cultivating new ones.

Willpower

Roy Baumeister has done the most in-depth research available on how willpower works. It's important for understanding the foundation of habit change. There are 3 crucial lessons about willpower you need to know in order to get you started on improving it:

- Your willpower works like a muscle – if you exercise it too much too soon, it gets worn out. Your daily willpower supply is limited and once you've used all of it up, you're done for a while. You'll need to "recharge."

- The more capacity for willpower you develop, the faster you'll continue to build it. Since you train your willpower by using it, consistently using willpower to make small positive changes in your life and exerting self-control on a regular basis in small ways, will help you strengthen it in other areas of your life. It will also slow the decline of your "daily supply," too. It's a two for one deal. You get more capacity and better "fuel mileage."

- You can (and should) set clear goals, but you need to leave some room for and plan around your willpower tank running low.

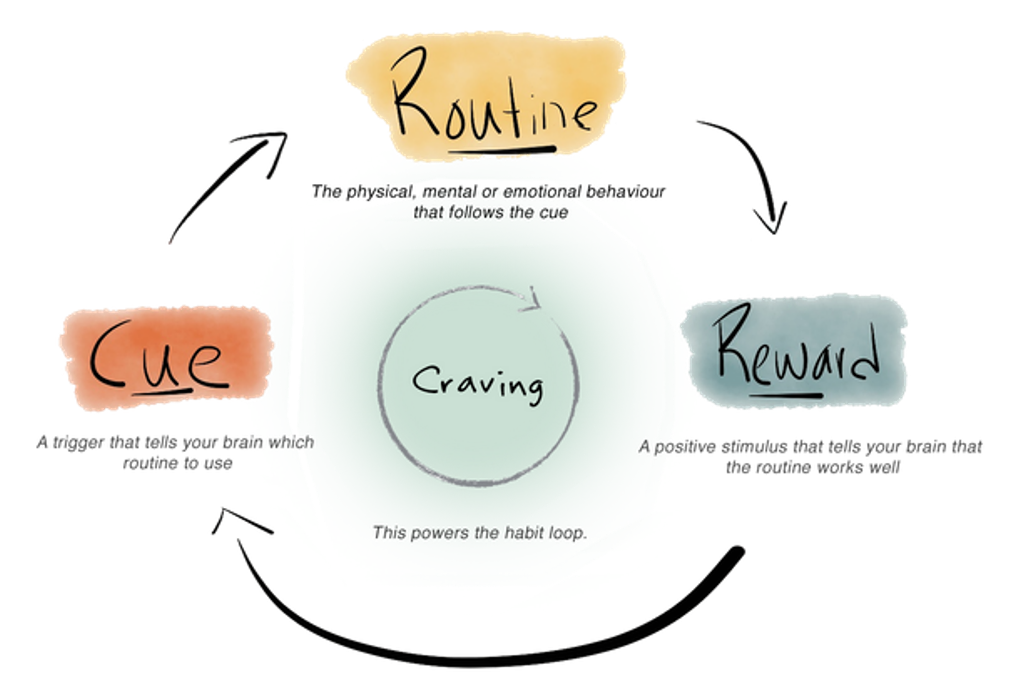

Elements of the Habit Loop

The Habit Loop is a neurological loop that governs any habit. The habit loop consists of three elements: a cue, a routine, and a reward. Understanding these elements can help you understand how to change bad habits or form better ones.

The Cue

The cue for a habit can be anything that triggers the habit. Cues generally fall into the following categories: a location, a time of day, other people, an emotional state, or an immediately preceding action. For example, every day at 2:30pm, someone could crave chocolate from the vending machine in the other building, or the smell from the coffee house downstairs compels someone to get a latte. For kids, the music from a roving ice cream truck is a very powerful cue. The cue tells the brain to go into automatic processing mode, and it takes effort to resist the cue, rather than get satisfaction from following the cue.

The Routine

A habit's routine is its most obvious element: it's the behavior you want to change whether that's smoking a cigarette, biting your nails or comfort eating. It's also what you want to reinforce like taking the stairs instead of the elevator or drinking water instead of snacking.

The Reward

The reward is the reason your brain decides the previous steps are worth remembering for the future. The reward provides positive reinforcement for the routine's behavior, making it more likely that you will do that behavior again in the future. The reward can be anything, from something tangible like chocolate, something less tangible like a half hour of TV or something with no "real" value like tokens or stars. Repeated rewards accumulate into an expected reward. Expected rewards take time and awareness to reset. This is related to how intermittent rewards work.

Short-Circuiting the Habit Loop

Because habit loops govern many of our automatic responses, short-circuiting a habit loop can be the means to overcoming bad habits. Charles Duhigg, author of The Power of Habit, suggests the following for reshaping bad habits:

Identify the Routine

Most habits have a routine that's pretty easy to identify: It's the behavior you want to change. Duhigg describes his own habit of going to the cafeteria in the afternoon to get a chocolate chip cookie and then sitting down with friends to chat. He had to work on identifying the cue and the reward.

Experiment with Rewards

The reward for a given habit isn't always as obvious as you might think. While the reward for a daily craving for a chocolate chip cookie in the afternoon could be just the cookie, it could also be talking with the people around the vending machine or an energy boost from the calories (which could be replaced with an apple or some coffee).

Experimenting with rewards is the time consuming part of hacking your habits. Each time you feel the urge to repeat your routine, try changing the routine, the reward, or both. Keep track of your changes, and test different theories on what drives your routine. In Duhigg's case, did he want the cookie or just want a walk? Was he hungry or was he just wanting to talk to friends? Every time you try a different routine; ask yourself after 15 minutes if you're still craving the original "reward." Duhigg discovered his craving went away after just talking with friends – he really craved socializing, and he figured that out by experimenting with the rewards.

Isolate the Cue

With the wealth of stimuli bombarding you every day, isolating a habit's cue usually isn't easy. Experiments have shown that habit cues generally fall into one of the five categories mentioned above, so to whittle down what could be triggering your habit, try writing down answers to the following questions (or at least answering them in some detail in your head) to see what pattern you get when an urge or craving strikes you:

- Where are you?

- What time is it?

- How do you feel physically and emotionally?

- Who else is around?

- What happened right before the urge?

Have a Plan

When Duhigg finished studying his chocolate cookie habit, he discovered that his cue was the time of roughly 3:30pm. His routine was to go to the cafeteria, buy a cookie, and talk with friends. The reward, he discovered, was not the cookie itself, but the opportunity to be with people he enjoyed. So, he created this plan for working around his habit: "At 3:30, every day, I will walk to a friend's desk and talk for 10 minutes." He then set an alarm on his watch for 3:30.

While implementing the plan had its hiccups, after a few weeks of paying careful attention to his new routine, he now does it unconsciously as a habit, one that's better for him.

Scientific Background

MIT researchers discovered the habit loop while experimenting with rats running mazes. They discovered that during initial maze runs the rats' brains generated a great deal of activity in the cerebral cortex. However, after running the same mazes many times, there was much less activity in their brains, even in the parts for memory.

The brain converts the repeated sequence of actions into a "chunk" or "program" in a lower part of the brain and saves the cerebral cortex for higher or more important functions. This is why when you get home from work after an uneventful drive, you often have no real memory of the drive. It's also why you don't remember if you turned the oven off or locked the front door on your way out.

(Elements of the above adapted from: http://habitica.wikia.com/wiki/The_Habit_Loop)

Questions to Journal

- What good habits do you have now? What good habits would you like to create?

- What bad habits do you have now? How interested are you in changing them? How much more motivation do you need to get started?

- What bad habits have you given up or tried to give up? What worked? What didn’t?

- What bad habits do you find yourself using to cope with stress or other negative emotions?

- What do you want to do this week to start a new good habit or replace an old bad one?

Videos

UMNCSH, The Science of Willpower: An Interview with Kelly McGonigal

Thomas Franks, 5 Lessons from "The Power of Habit" by Charles Duhigg

Motivation2Study, How To Stay Motivated & Break Bad Habits

Resources

Judson Brewer, MD, PhD, Unwinding Anxiety: New Science Shows How to Break the Cycles of Worry and Fear to Heal Your Mind (2021)

James Clear, Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones (2018)

Charles Duhigg, The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business (2014)

Kelly McGonigal, The Willpower Instinct: How Self-Control Works, Why It Matters, and What You Can Do to Get More of It (2013)

Roy F. Baumeister and John Tierney, Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength (2012)

Verses for the Week

Philippians 4:13

I can do all things through him who strengthens me.

Romans 12:2

Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may be able to discern the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.

2 Peter 1:5-8

Make every effort to add to your faith goodness; and to goodness, knowledge; and to knowledge, self-control; and to self-control, perseverance; and to perseverance, godliness; and to godliness, brotherly kindness; and to brotherly kindness, love. For if you possess these qualities in increasing measure, they will keep you from being ineffective and unproductive in your knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Prayer for the Week

Help me this week to replace the habits that hurt me and those around me with habits that build us up. Help me build new habits that make my life stronger, happier and more energetic. I want to be an example to those who know me. Amen.